Mequitta Ahuja

We talked to Mequitta Ahuja, a contemporary American painter based in Weston, Connecticut and in Baltimore, Maryland. Her work is deeply influenced by her life - her mixed heritage, birth of her son and death of her mother. Mequitta takes us through her process, explains some of her work and tells us what inspires her the most.

You position yourself in your compositions and create pictures inside pictures, stories inside stories. This is really peculiar and unique. What does your creative process look like?

My mission is to change expectations of the self-portrait especially the self-portrait of a woman or a person-of-color. Women and people of color are expected to mine their personal biographies as case studies in our social condition. I aim to hold and to embody in my work both politics of identity as well as the function of self-portraiture exemplified by Poussin’s famous self-portrait – displaying authority within the field of painting including its history. This is where my use of pictures within pictures come from. My creative process is multilayered, and by depicting myself with my own art, I show the iterative nature of artmaking from source material to final work. In my works, I show the influence of other artists and past eras of painting, but the works I depict are always my own.

Your self-portraits also have another dimension. You are not presenting yourself in something that would be considered a standard self-portrait. You are an artist. We can see you as a working woman and a mother in front of her creation - both her art and her child. Is this a response to a classic representation of women, and specifically women of color through art history?

I replace the common self-portrait motif, the artist standing before the easel, with a broader portrait of the artist at work. I show myself/my subject in the studio reading, writing, handling canvases and holding my source material, such as photographs and drawings. This strategy of pictures within pictures allows me to work across modalities of painting—abstraction, text, naturalism, schematic description, graphic flatness, and illusion. By positioning a woman-of-color as the primary picture-maker in whose hands the figurative tradition is refashioned, I knit my contemporary concerns, personal and painterly, into the centuries-old conversation of representation. We–women, people of color, mothers–are not only experts on ourselves and on our social condition. I am also an expert on art. My paintings tell you what you need to know about paint - its form, its conventions and its history. As women, as people of color, as mothers, we too can embody that authority.

You have a very unique style layered with your multicultural heritage and at the same time, your paintings look like dialogs with certain art periods. The one we notice the first is your relationship with cubism. Le Damn Revisited and Xpect both look like a response to Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and his appropriation of African objects. How did you come up with this idea? What is your relationship with dominant narratives in art history?

I made Le Damn Revisited and Xpect because I was invited to participate in an exhibition at the Phillips Collection called Riffs and Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition. A thoughtful review of the show can be read here: https://editions.lib.umn.edu/panorama/article/riffs-and-relations/

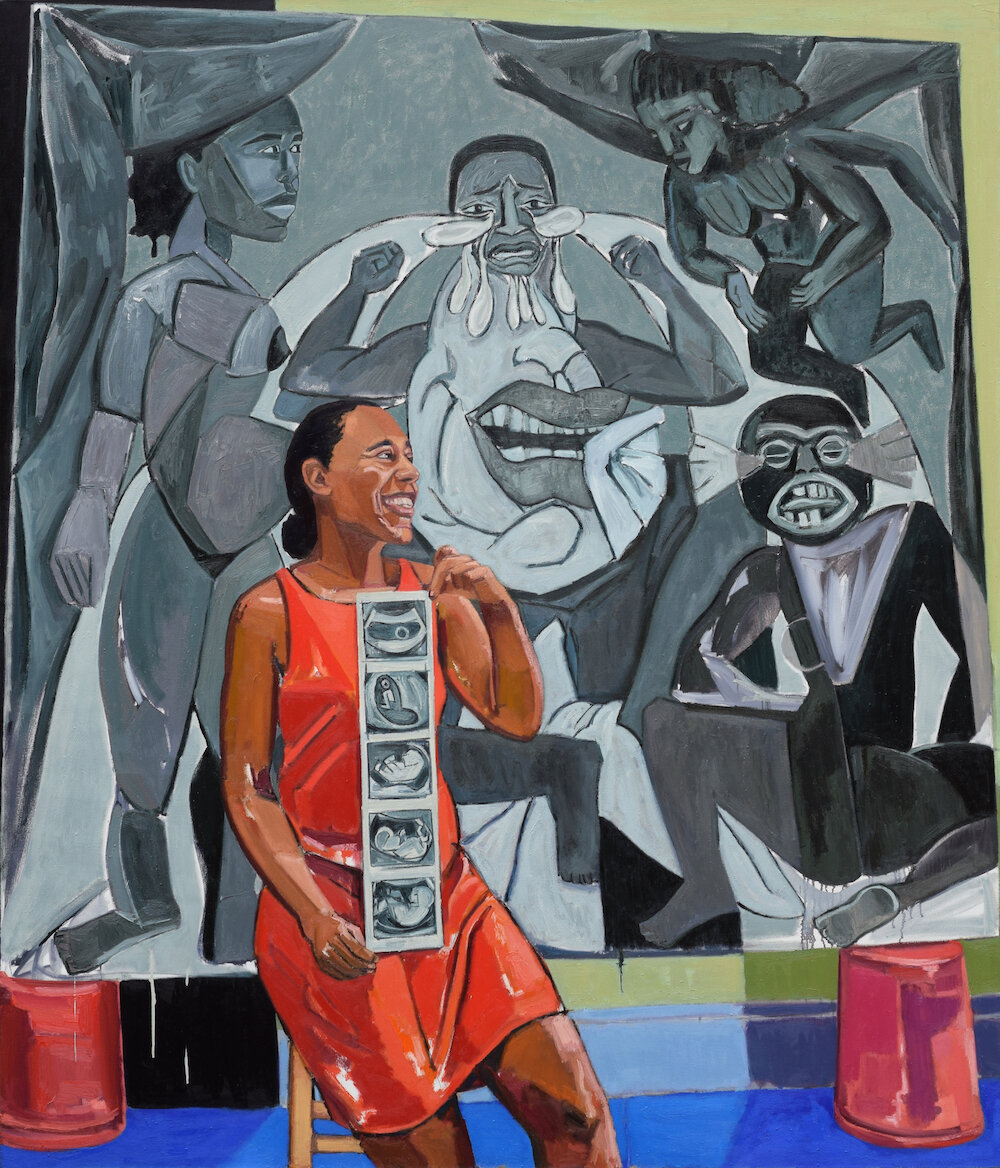

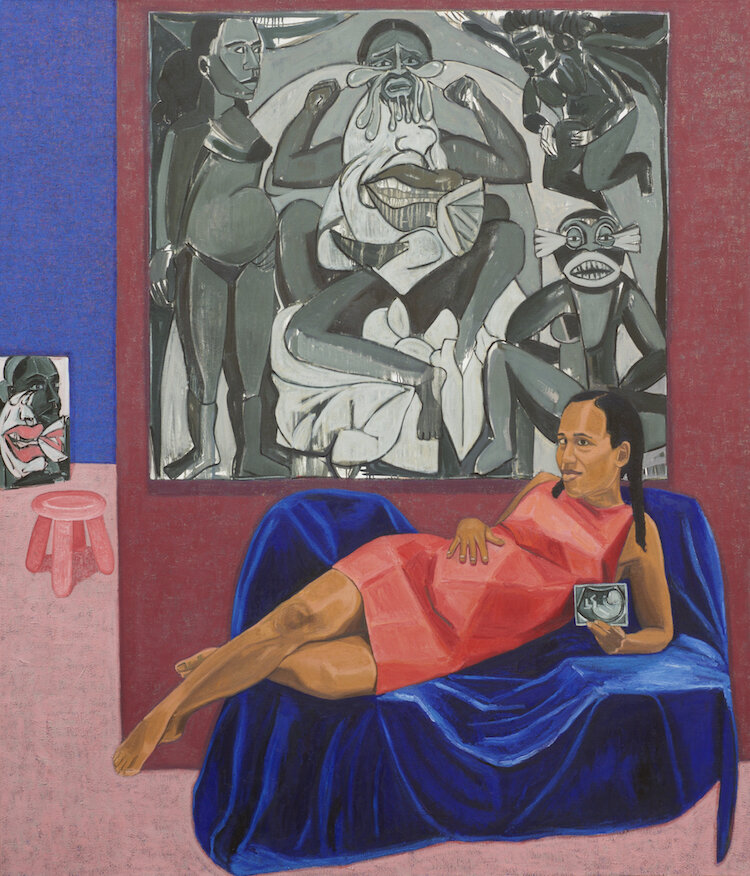

In both paintings Le Damn Revisited and Xpect, I chronicle my journey to motherhood. The gray-scale painting within the painting is my rebuttal to Picasso’s 1907 painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Picasso’s painting is about the threat and allure of sex. Picasso presents woman—her body and her seduction—as an embodiment of that tension. I, too, address the threatening aspect of sex, but from a woman’s point of view. In my rebuttal to the Picasso, I depict my range of feelings from determination to despair throughout my process of trying to conceive. In Xpect and Les Damn Revisited I conclude that story with a declaration and celebration of my pregnancy.

My work is a form of tribute, analysis and intervention: tribute, out of sincere admiration for the figurative tradition; analysis, by making something vast comprehensible to both myself and to my viewers and intervention, by positioning a woman-of-color as primary picture-maker and a challenge to the expectations of who are or get to be “masters” of pictorial representation.

Where do ideas for your paintings come from?

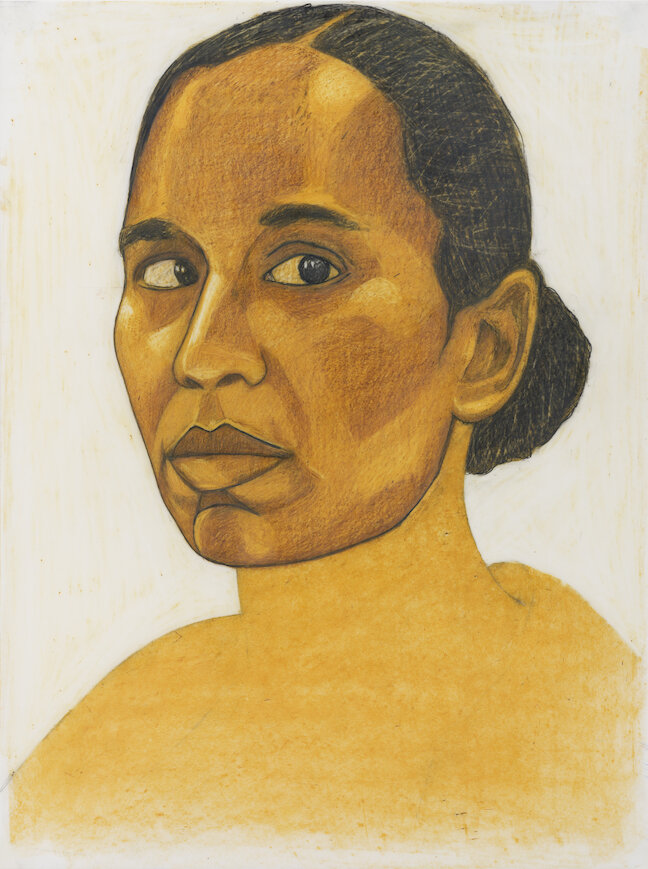

My sources are my lived experience—my mixed Black and Indian heritage, the birth of my son, the death of my mother–and they are the figurative painting tradition, and they are my own art–which echoes both: life and art.

I repurpose painting ideas across time and geography including Egyptian form, Pop Art, Giotto frescoes, Folk art, Provisional Painting, Hindu figuration and early American painting. New ideas are also organically generated by my iterative process of working, in which my unanswered questions in one work give rise to new works. In part because my studio habits are daily and routine, I don’t experience creative blocks

Which artists have influenced your work the most?

In addition to Poussin’s 1650 self-portrait in which he positions himself as the authority on the history and discipline of painting, the predecessors informing my approach are Velasquez, Kerry James Marshall and Doris Lessing. For readers of Lessing’s 1962 novel about living in the world as a woman and an artist, The Golden Notebook, Lessing, through her main character’s color-coded notebooks each with a specific writing style and purpose, shows the complex interrelation of artist’s experiences, feelings, intellect, and craft, thereby enacting the relationship between art and its genesis. Using paintings within paintings, I enact the same.

We are at the end of 2020. How did this year affect your work process?

My life has changed dramatically, and this has changed my art. When our son was two and a half weeks old, we learned that my mother had an aggressive form of uterine cancer. In 2019, we moved to be near her, purchasing the house just behind my parents. In the time I spent playing with and caring for my son, my parent's only grandchild, I also got to spend time in intimate, daily connection with my mother, who passed away in May of 2020. Prior to these life changes, I had been trying to loosen up in the studio. My new circumstances tipped the balance. Working with time constraints forced me to approach figuration gesturally. Working while in the midst of a process of grieving forced me to find its material embodiment, replacing my additive process with erasure–a subtractive method. In my recent work, I make paintings by scraping away paint. What’s left behind–that’s the painting. At first, it surprised me that during this tumultuous time, qualities I have long sought in my work are coming to fruition, yet it is a testament to the essential role of art in my life. Ever cognizant of the professional, historical and intellectual field in which I work, art is also where I go to process my lived experiences. It is my container for everything.