Simona Ghizzoni

Let's start from the beginning, how you first started taking photos. In another interview that you gave, I read that your first camera was a Minolta that you found in the trash and I thought: there's something I have to ask about. What can you tell our readers about how you discovered photography?

Ha, that story! I was very young, didn’t have much money in my pocket and while studying at the University in Bologna I was working as an assistant and cleaner in a tattoo studio. The owner of the shop was really obsessed with cameras. One day while I was cleaning I opened a closet and to my amazement it was completely full of cameras, some broken others just old, stacked on top of each other carelessly.

I took the one Minolta, get it repaired, bought a couple of used lenses and that was my first camera. Photography, though, had already entered my life a few years earlier, in my last year of high school, thanks to the books I had discovered in the municipal library of my hometown. I used to photocopy the images I liked the most: Diane Arbus was my very first love. I saw something beautiful and terrible in her images and deeply wished I could find that something for myself as well.

You wrote that "la fotografia è la più selvaggia, la più libera, la più irresponsabile di tutte le cose" ("photography is the wildest, the freest and the most irresponsible thing") and that, for you, photography is means of expressing doubt towards reality. If you were an abstract painter this would make all the sense in the world, but when it comes to photography, it may not be obvious to everyone. How do you achieve that with photography?

Those words are from an audio recording by Virginia Woolf in which she tells what language means to her. Those words resonated. Photography was born as an extraordinary scientific discovery, destined to change the way we see and therefore interpret the world around us. We’ve been told it was an objective reproduction of reality and we believed it. But already from the second half of the IXX century some things began to go in another direction. On the one hand, the idea that photography could accurately measure everything, even man, led to the aberrations of colonial photography, just to cite one of the most glaring examples. On the other hand there were authors who used photography to recreate tableau vivants, esoteric images and even portraits of ghosts.Therefore, I reject the idea of photography as an objective and neutral documentation of reality, and instead I welcome a vision of photography as an interaction between the photographer and the external world, in which both are modified as they meet.

For me photography is a space of freedom and even a possibility to rewrite reality.

Your work is really emotionally impactful, at least that's the effect it has on me. How did your style develop? When you look back at your career, how did you arrive at the place where you're at now?

Thanks! I have to tell you, though, that I haven't always cherished this very instinctive and emotional way of working I have. In fact, I was embarrassed for many years to show some of my photographs, I was sure that my fragility would emerge from the images and that I would be even more vulnerable.

So I think I've found my style...in spite of myself.

My work revolves around two major themes: the condition of women, which also sees me engaged as a visual activist, and the self-portrait, which is for me the necessary counterpart, a constant reflection on myself and the world around me. These two themes are an urgency and so I consider them the compass that allows me to move forward in the chaos of life and through all the changes that occur.

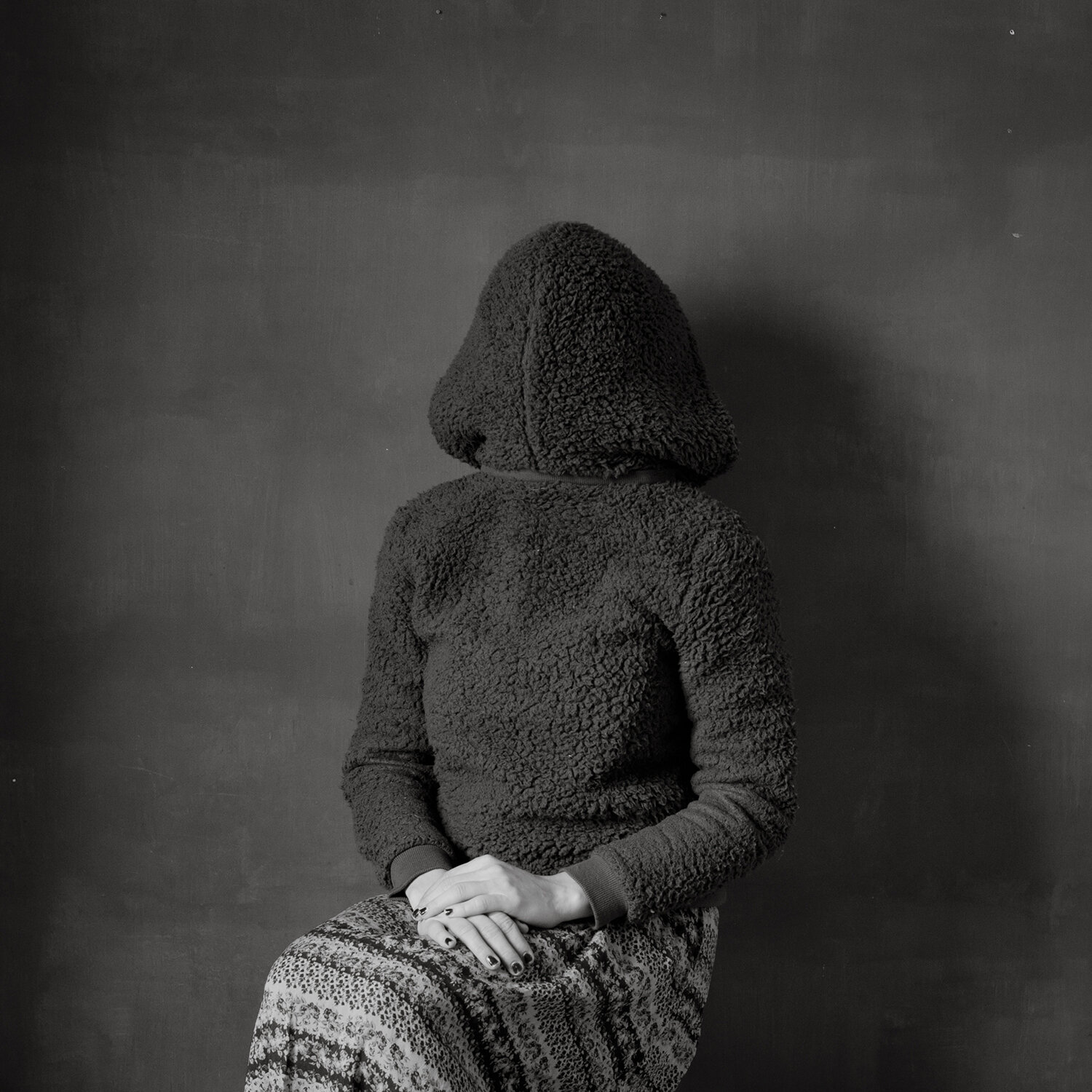

You've done several series of photographs cumulatively titled Self-Portraits. I'm referring to your series Tutto parla di te, Isola, Aftermath, etc. They are really interesting and perhaps even confusing insofar as almost not a single one is what we would normally think of when we read "self-portrait". In fact, in those instances where they actually contain humans, their faces are obscured, their bodies fragmented, they're standing behind objects or are obscured by curtains. Often there is evidence of humans like a teacup, a basket of fruit, etc. It's almost like the actual self-portrait is in the composition, the light, those elements you can't quite even name, but you can feel. How did these photographs evolve and what inspired you to make them?

I began working with self-portraiture instinctively. As a teenager I suffered from an eating disorder. For the almost 10 years of the illness, there were no photographs of me. I refused to be seen by an outside eye, busy as I was bargaining with my inner one. To heal, I needed to learn to look at myself again. Self-portraiture, as I said earlier, is a constant process of reflecting and rewriting my personal story. If I don't know what kind of person I am, I can't possibly know what kind of photographer or artist I can be. But you're right, in fact there is only one series, called In Between, which contains exclusively self-portraits. My autobiographical narrative is composed of many fragments and metaphors. Animals, plants and waters have always been a great source of inspiration for me. In fact, since I was very little, I used to invent worlds populated only by animals in which I was the only human allowed to enter. I guess I didn’t move much from there, except for the fact that now I am very conscious of the impact we have, as humans, on our natural habitat.

Over the years, you've photographed women's lives in places like Gaza, West Bank, Jordan, Western Sahara, etc. The resulting photographs are haunting and profound. I'm wondering if it's possible to make all those photographs and have the experience behind them and leave unchanged. What have these places taught you?

I am the first woman in my family not to have experienced a war. My grandmother was born during World War I and gave birth to my mother in World War II.

My maternal family was a peasant and lived in a small mountain village, near a bridge. During the last war, the bridge was often the scene of ambushes and retaliations between the German army and the Italian resistance.

When my mother was just born, sometimes my grandmother was forced to take her to sleep in the woods, for fear to be killed.

I have never forgotten these tales of war times from the women's point of view.

Unlike men, women rarely went to the front-line, but they had to be always ready to face the daily consequences of war, trying to maintain a sense of normalcy in the life of the elders and the children.

Researching the origins of my maternal background was the real trigger to tell the story of war from a women's perspective. To get to your question, I really can't list everything I've learned, and how much working for years in conflict zones has changed me.I probably don’t even know it yet. The work of photography to me is an exchange and I don't think the photographer can or should come out of it untouched. But one thing above all, I discovered the kind of women I love to photograph: women who have gone through enormous hardships but have turned their pain into concrete change.

Photography seems to be a way for you to process your own emotions and heal. One such instance is your series Odd Days that deals with eating disorders. The intensity and rawness of those photographs speaks for themselves. It's also easy to see them as a social commentary, even a political one. But as someone who struggled with bulimia yourself, what did it mean to you to create this series?

Odd Days has been my real first work. Healed from bulimia I felt the need to retrace my steps and try to see from the outside the hell I had gone through. I didn't have any pictures of myself during the period of the disease, as I mentioned, so I decided to meet other people and tell a collective story about eating disorders in which I could see myself reflected as well. It wasn't easy, at times I had difficulty keeping my role steady, distinguishing the photographer from the ex-patient. That's why it's a very slow process, a work that in some chapters has been going on for more than 13 years now, as in the portraits of Simona Giordano, whom I met in one of the treatment facilities I visited and who has become one of my dearest friends (and yes, we even have the same name).

With Odd Days I also achieved a new awareness about myself. I began to not be afraid of talking about my experience with eating disoders and to realise that my point of view was privileged and could bring about a real change in how such disorders are represented in the media. So yes, it is all about healing.

Your photography can be deeply personal but it's also political, although not in what I would call an explicit way. It's hard to put into words what I mean - when I see the photos from Uncut or your journals from Gaza, I don't feel like you're preaching. There is something very powerful in your approach. You consider yourself an activist. Striking the balance between aesthetics and politics isn't always easy. What is your approach?

What visual activism means to me is mainly a reflection on the role of the image in the contemporary world. On the one hand, there is the choice of themes to deal with, a choice that is never made lightly but that always calls into question the perspective and the urgency of telling a specific story. Then there is how to tell a story, and for me the method is the essence. The relationship with the photographed subjects must be a dialogue, in which my task is mainly to listen, trying never to intentionally or unintentionally exploit the pain of the other. I refuse the idea of the “invisible photographer” as a pure witness of the facts. On the contrary, I want to involve myself and my presence to actively become part of the story and possibly effect a change, even the slightest, in the perception of a certain topic. I am the first one who needs to keep questioning my approach, the stereotypes and prejudices in my own work.

Finally, part of my activism is in the choice of where to disseminate my work: together with the journalist I have been working with for many years, Emanuela Zuccalà, we have made it a priority to bring our work to institutional and political venues, such as the parliament in Brussels and Strasbourg, as well as on the pier of Coney Island together with #Dysturb.

Your photos seem very intimate even when the topics aren't necessarily such. What is your creative process like - do you work alone or with a team?

The answer is very easy. If something doesn’t matter to me, I don’t see how I should convince someone else it matters. So when I choose a topic, it has to become personal, I need to know everything about it, and relate. I work mainly alone and have never had an assistant. I tend to spend a lot of my time alone anyway. But especially when I photograph I need to create an intimate space, a sacred space and give time.

Do you have a favorite photograph (of the ones you took)?

Not really, but I am very attached to the image of the giraffe in the series Aftermath. That giraffe has a long history. I found it in a zoo in northern Italy and it struck me as being so out of place. She was running around in circles, in what looked to me like a decayed theater. At the time, I was reading the story of Zarafa, the first giraffe ever seen in Europe. It arrived in October 1826 on the dock of the port of Marseilles, a gift from the Viceroy of Egypt Mehmet Ali to the King of France Charles X, and traveled across France up to Paris. An extraordinary sight for men, but a great suffering for her. Since this encounter I began to reflect more and more on the relationship we have with nature and animals. The photograph is part of a series that is printed in black and white and hand-painted by me, so I have a relationship with this series of images that is also very physical.

Some of your photographs are black and white, others in color. What drives these decisions for you?

The decision is made for purely artistic reasons. The works you've seen develop over a period of fifteen years, and over time I've gone through more "abstract" phases, in which color seemed to distract me, to phases in which I felt the need to return to an aesthetic more akin to that of the “everyday photography”. Even in this second case, however, there is always little that is random in my images. The only rule, is that the choice must be made before starting a new series, because the way of shooting in black and white requires a very different process for me than color.