Viviana Peretti

Viviana Peretti is an Italian photographer whose career and life are based between Bogota and New York. She studied anthropology and journalism which layed the foundation for her photographic work in the field of social rights, LGBT rights and even in the way she explores the human body.

Her work has been exhibited across the world from the National Portrait Gallery in London, the Rita K. Hillman Gallery in New York to the Museum of Art and Culture in Bogota, and many more.

On your web site there is a short bio and the very first sentence implies an interesting story, an intersection of different cultural and political influences. You are an Italian photographer, but you split your time between Bogota and New York. How do these different cultural contexts influence your work?

I left Italy twenty years ago and moved to Colombia, a country that surprised me in both good ways and bad: huge cities, incredible landscapes, wild nature... but also a lot of abuses and impunity. Since my arrival, I have been moved to document human rights violations on the one hand, and, on the other, abuse committed against LGBTI people who, to live freely have to move to big cities, leaving behind their families and their roots. Later, I spent three years traveling throughout the country, taking photographs of cemeteries as a metaphor for the country: its chaos, lack of regulations, and, on the other end of the spectrum, its unexpected magic. New York, on the other hand, was a bit disappointing in terms of human interactions. In the beginning, I felt really lonely. Surrounded by eight million people, but alone nonetheless. Desperate Intentions, my first series about New York, represents my attempt to document the human disconnection I experienced. I later learned to navigate this solitude and take advantage of it. In New York, I also focused on religious communities, kinds of ghettos, that strengthened my idea of a city full of enclaves. Communities where faith binds people together, at the same time as it segregated them from the rest of the city. I think there are subjects —religion, mourning processes, LGBTI rights, and life in big cities— that interest me regardless of where I am based.

Let's talk about Colombia, first and foremost because I think we both share a lot of admiration for Gabriel Garcia Marquez. You even use the verb "macondiar,” or in its gerund form, "macondiando.” The nerd in me can't resist but ask, what do you mean by it, and how can we see that in your photographs of Colombia?

Macondo is a fictional town that Gabriel García Márquez invented for many of his books, in particular for One Hundred Years of Solitude. It is a lonely, isolated town, full of absurdities. A remote place of fantasies that are real and realities that are imaginary. A symbolic place, a metaphor of Colombia. ‘Macondiando’ is a verb I made up based on that imaginary place described by Márquez. ‘Macondiando’ describes situations where anything can happen, where reality sometimes is so absurd, weird, and crazy that it goes beyond any stretch of imagination. And sometimes, when faced with such craziness and dysfunctional reality, the only thing you can do is surrender and go with the flow. I was thinking about a hashtag that could describe all my mixed feelings about Colombia and ‘macondiando’ came to mind. The idea behind ‘Macondiando’ is to evoke a country that can be felt like hell and heaven at the same time.

There is a particular aspect of your work that I really like, and that's your iphoneography. There is a kind of intimate, fragmented and even nostalgic feel to those photos, they seem like a kind of a journal, something only accidentally exposed to the public. As an artist, what is the difference in creating with an iphone as opposed to a professional camera?

I firmly believe that what makes a photographer is not the tool she uses, but her eye, her sensitivity and, if she really has something to say through her work. Apart from the technical limitations of an iPhone, I don’t think there is a huge difference. In fact, in recent years, I have used the iPhone not only as a notebook for my personal journey in life, but also for my photojournalistic work. What I like the most about working with an iPhone is that I always have it on me, and people are really relaxed in front of it. More relaxed than in front of a professional camera that can sometimes be a bit intimidating. I generally use it with an app that allows me to shoot with a square format, just like I do with my Holga cameras or my Rolleiflex. And I like to use it with all the limitations of a simple point and shoot without the possibility of adjusting the aperture or shutter speed. In some ways, working with an iPhone is also a way to keep training my eye. A training that I then apply to my analog work.

Help our readers situate your work in a context. What are some of the artists you admire and that you feel have influenced your work?

I think a lot of influence comes from Italian neorealism. And it is quite an unconscious influence. When I was a teenager, I used to spend parts my of summers watching Italian movies with my siblings, movies by directors like Rossellini, De Sica or Risi. These black and white movies portray stories set among the working class, with non-professional actors and filmed on location. Most of the stories were related to the difficult political, economic, and social situation in Italy after World War II. In photography, I admire the work of Sergio Larrain, a Chilean photographer that was a master of street photography. In New York, I discovered Robert Frank’s Americans. Among contemporary photographers, I really like what Jungjin Lee is doing as well as Jack Davison’s work.

You have degrees in anthropology and journalism, and thinking about those two, they seem like an excellent foundation for a photographer! How did you first encounter photography and how did you realize it's your medium?

I always had a ‘secret love’ for photography but at first I didn’t consider the possibility of pursuing it as a career. More than twenty years ago, in Salamanca, I saw Sebastião Salgado’s exhibition on the drought in Sahel. I was really moved by the photographs and I left the exhibition with the dream to be able to one day tell stories in that powerful way. In 2000, I arrived to Colombia to do a master’s degree in anthropology in the south of the country. For security reasons, I wasn’t able to do so and I ended up spending two years in the darkroom at the Universidad de Los Andes in Bogotá and taking all the photography classes available there. The realization that photography was my medium came thanks to Magdalena Agüero, an amazing teacher I met at the University. She saw one of the first rolls I shot on the streets of Bogotá and she said, “I am afraid you will have to change your profession.” Magdalena’s words were a revelation and gave me great strength to continue pursuing my dream of being able to tell stories, and reveal myself, through images. What I love the most about photography is the universality of its language that doesn’t need words and verbal elucidations.

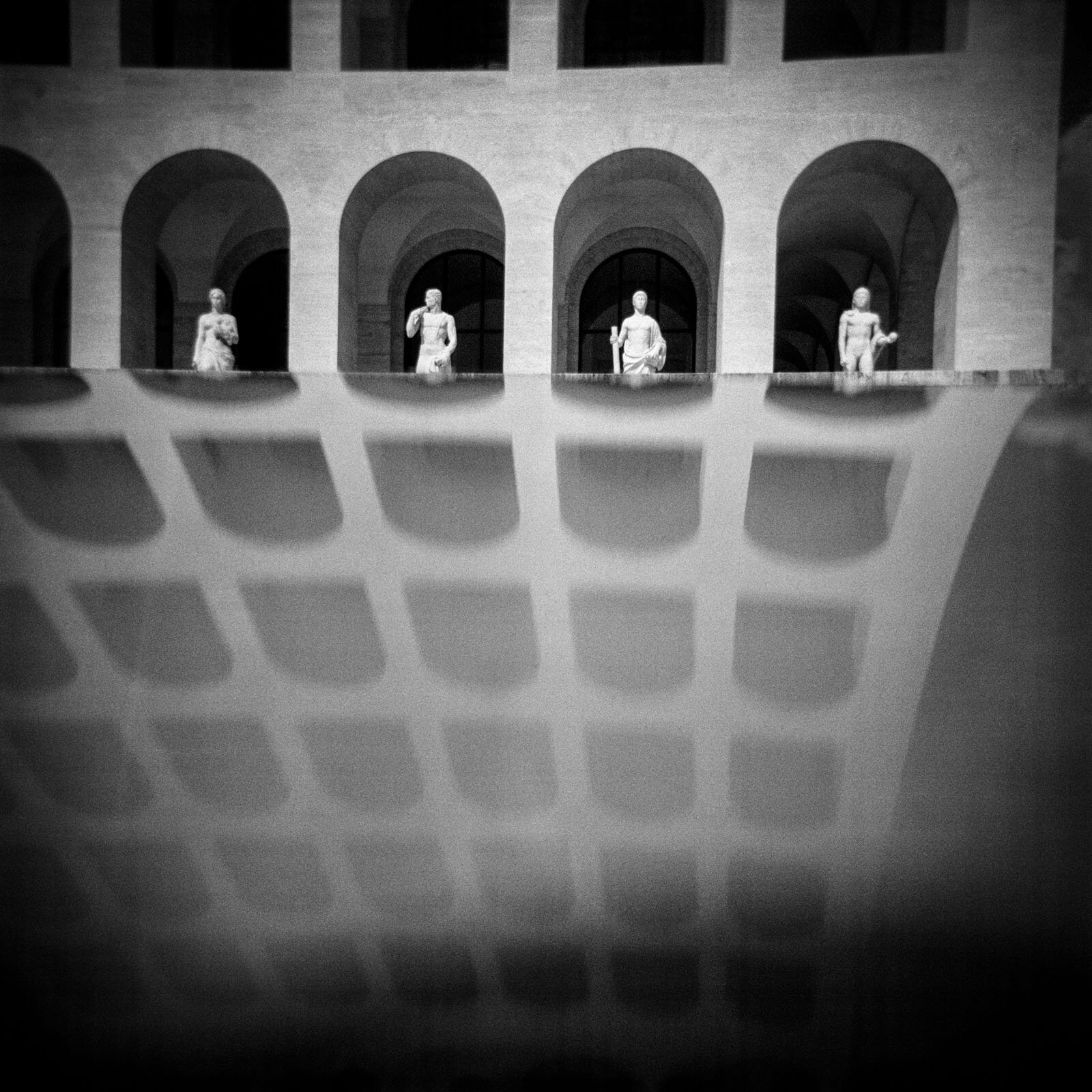

How would you describe your approach to photographing different places? To put in a slightly more pretentious way, what's your process? Speaking about cities that I know well, Rome and Genoa, in your photos you manage to avoid every platitude, every cliché and even the "everyday beauty" that you would necessarily encounter as you go about the city. Instead, you focus on corners, moments, details...

I respond to places by taking pictures. There is never a plan; maybe there is a general opinion about a place but never a preconceived idea about what I am looking for. I just walk, walk, and walk, chasing light, forms, and shadows. I just respond to what I see by taking photos of it. It is something really simple: I am just reacting visually to what is outside. And that reaction is deeply connected to my background, the things I believe in, my mood that day. It is a very personal journey. So, in the end, what comes out is not an objective portrait of each city, but just ‘my’ Rome, ‘my’ Genoa, ‘my’ Marseille’…

Your series of photos Body Memories is particularly striking. In it you juxtapose the human body with landscapes, walls, curtains, concrete, etc. There's a particular kind of gentle power and resilience that emerge there. How did you develop this series of photographs?

In 2015, while I was a fellow at the Camargo Foundation in Cassis, a small village in the South of France, I met Wen Hui, a Chinese choreographer and dancer. Wen Hui introduced me to the concept of the memory of the body which sets out that the body itself is capable of storing memories, as opposed to only the brain. By dancing, Wen Hui transforms her memories into moves. The series is a dance between Wen Hui and my camera and between her memories and mine. It is a tribute to our bodies and their special, unique way of experiencing and remembering life. A hymn to our bodies as extreme examples of 'otherness' where the negative and positive poles merge and combine: Yin and Yang, passive and active, female and male, Moon and Sun. I used double exposures because I also wanted to include the seascape and the memories of the amazing place where we both enjoyed the privilege of being artists-in-residence. The double exposures were done in the camera and not by using any post-production program. So, I also had to make some extra memory work to remember the position of Wen Hui’s body in the first photo in order to compose the second photo and have a perfect combination of the two in the final image (the only image that exists. Neither the first, nor the second photograph exist as single images).

Other than Body Memories you touch on the body and gender in other photographic series too, Miss Gay Internacional and Dragstar come to mind, and perhaps Superheroes to an extent as well. It seems that beauty, dignity and strength characterize many of your subjects. Consciously, how do you approach photographing the human body?

The idea for Body Memories, emerged through my work with Wen Hui. I wanted to evoke what the concept of body memory represents, and I wanted to talk not only about Wen Hui’s memories but also my own, along with the memories of where we were living at the time. I used to visit Wen Hui’s apartment really early in the morning and take photos of her while she went through her dance routine. There was no script. She was dancing and I was dancing around her with my camera in order to capture her movements, and our memories. The same happens with my other works where I photograph the bodies of LGBTI people. I never direct my subjects. Once again, it is just action and reaction. A sort of dance. I generally follow people in their daily routines and take photographs of what makes sense to me. I avoid asking my subjects to pose or do things for me. I am just there. I observe their actions and interactions with other people and when something magical is about to happen, I raise the camera and take my photograph. I try to be not the famous fly on the wall but a silent, discrete one moving around. And obviously, I try to be very respectful of the dignity of my subjects. In the case of the LGBTI population in Bogota, I avoid taking pictures that violate their privacy and intimacy. At the end of my work with Wen Hui, she told me that, despite being naked, she never felt vulnerable in front of my camera.